Swastika Night by Katharine Burdekin: the novel that predicted Incels?

‘As a woman is above a worm,

So is a man above a woman…

As a woman is above a worm,

So is a worm above a Christian’

This doggrel summarises the victorious Nazi hierarchy described in a 1937 novel by feminist writer Katharine Burdekin: Swastika Night. It is set over 700 years in the future, and would now count as an alternative history. It is an equal parts fascinating and frustrating story about fascist ideology pushed to its logical conclusion. Burdekin focuses on aspects of Nazism that don’t get much attention in popular portrayals: its attitude to and treatment of women. This gives her novel a strikingly contemporary tone, given the current overlapping of far-right politics with the intense misogny and status anxiety of (among others) the ‘Incel’ and ‘Men’s Rights’ movements.

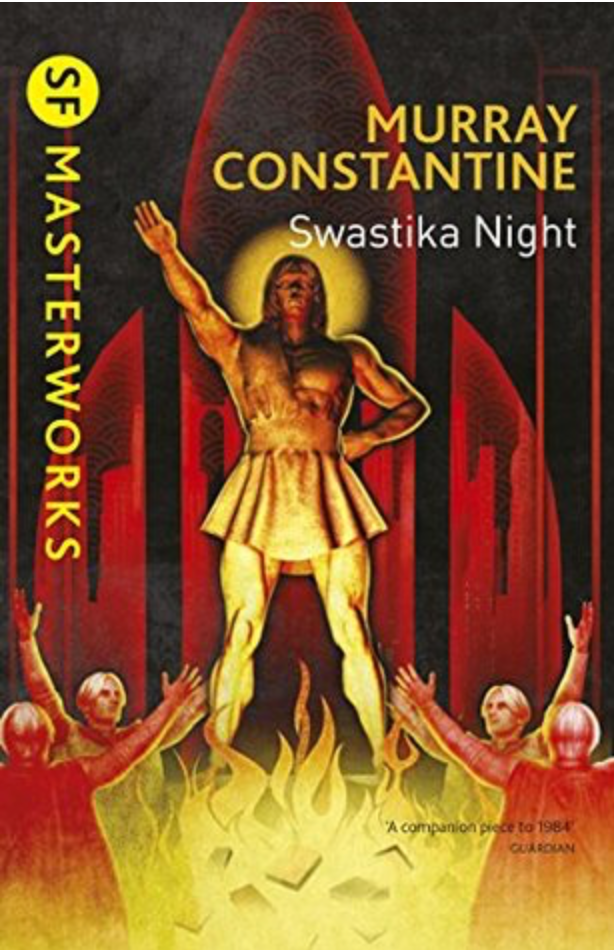

Burdekin started writing under the pseudonym Murray Constantine in 1934. A committed anti-fascist, she was conscious that writing against them risked violence against herself and her family. She had been briefly married to the Olympic Rowing champion Beaufort Burdekin so had some public profile. So carefully was the true identity of ‘Murray Constantine’ concealed that her work was attributed to other (male) writers.

Plenty of historical scholarship discusses how Nazism wanted to reduce women’s role to ‘Kinder, Küche, Kirche’ (‘children, kitchen, church’). Such was regime’s dedication to maintaining traditional gender roles that even its wartime mobilisation suffered from an initial reluctance to allow women to work in heavy industry. However, Nazism’s focus on returning to ‘traditional values’ in gender relations often gets missed because it doesn’t come across as distinctively ‘Nazi’. Plenty of contemporary politicians campaign on causes such as restoring family values, getting back to basics etc. Burdekin, however, saw not only traditionalism, but a cult of masculinity, as central to the Nazi world-view. ‘What if Hitler won?’ is a popular alternative history scenario — most recently seen in the TV adaptation of Philip K Dick’s The Man in the High Castle. However Burdekin is writing in the 1930s, so her question is ‘what if Hitler wins?’. The future Hitlerian society she describes— the ‘Holy German Empire’ — is rigidly hierarchical in class, nation, and race terms, while women are seen as animals with no souls. After a historical event called the ‘Great Reduction’, women in this world have been dehumanized and live in camps where they only subsist, submit to men (rape is not a crime), raise their female children, and have their male children taken away at eighteen months. Men, particularly those with high status, are taught to regard women with utter contempt — with (heterosexual) sex as a necessary, but ‘dirty’ exercise for procreation (though the book shows actual attitudes often differ from the official line).

Swatiska Night predicts both World War II (with a different outcome), and the Holocaust of the Jews (though Burdekin, writing in the 1930s, doesn’t use that term). Burdekin also speculates (anticipating The Man in the High Castle) that after an Axis victory the world would be divided between Germany and Japan. Given the huge significance of the Holocaust in contemporary views of Nazism, Burdekin’s treatment of the destruction of the Jewish people comes across as a bit perfunctory, as it is mentioned only as a prelude to Nazism’s persecution of Christians and women. However in the world of this book it is an event over 700 years in the past. It is also 600 years since a kind of Nazi Cultural Revolution has wiped out historical memory as we know it. Hitler is revered as a seven-foot-tall blond, blue-eyed, bearded deity who was born from the forehead of ‘God the Thunderer’. Indeed one of the characters has a crisis of belief after seeing the last remaining actual photograph of Hitler — whom he is shocked to discover not only looks like a normal human, but also stood in the physical presence of women (a defiling act in this world).

Christianity has survived Nazi persecution — with its adherents as despised outcasts. Its theology has evolved over 700 years to incorporate a belief that Christians are now being punished for their persecution of the Jews. The official Holy German religion has four ‘arch-fiends, whose necks He [Hitler] set under His Holy Heel’ : Lenin, Stalin, Rohm, and Karl Barth. Ernst Roehm was an early Hitler ally and leader of the Nazi’s SA militia, who was purged in the so-called Night of the Long Knives. Karl Barth is a more obscure figure. A theologian who set up the underground ‘Confessing Church’ in 1930s Germany, Barth wrote the Barmen Declaration, which attacked mainline Christians for capitulating to Hitler. Barth insisted that true Christians could only give allegiance to God. While it’s not clear if, as Michael Moorcock suggests, Burdekin thought Christianity could beat Hitler, she gives it more staying power than socialism. As can be seen from the quote at the start of this article, Christians are so lowly that even women (and worms) outrank their status.

Notably absent from arch-fiend list is the United Kingdom. Burdekin was writing at a time when the spirit of appeasement with Hitler was strong in the UK. She makes the point in Swastika night that, as an Empire itself, Britain wasn’t in a good position to condemn Nazism’s ambition to build another one.

The story is told almost entirely from the male characters’ perspectives — and they are unreliable narrators. Von Hess the ‘Teutonic Knight’ (the top of the social order); Hermann the ‘Nazi’ (now the name for a kind of intermediate, functionary class); and Alfred the Englishman (a subject of the Empire and therefore a notional racial inferior). The novel’s second half is made up of their conversations about a book — the last book on earth — which contains the ‘real’ history of their world. The characters express views on femaleness that make for uncomfortable reading, however Burdekin is making the point that the degradation of women is also degrading to men — something the male characters have to figure out for themselves. Ultimately the future of humanity is being threatened by the lack of female children being born — a point which makes Alfred, the dissident of the story, radically re-evaluate his beliefs.

Another uncomfortable aspect of the book for contemporary readers is its attitude to homosexuality — which is presented as a common practice in the dominant masculinity of the Holy German Empire. Burdekin (who was likely in a same sex relationship herself) isn’t homophobic — indeed for one of the characters same sex attraction starts them on the road to dissent. As Thomas Horan writes, Burdekin ‘introduces hope for ethical renewal via queer desire’. Hermann, the loyal German youth, loves and pines for the dissenting Englishman Alfred. However, homosexuality in Swastika Night is also linked to Nazism’s cult of masculinity, which Burdekin is taking to its extreme conclusions. The homophobic record of the Nazi regime is beyond dispute, as one of its first acts was to order the police ‘pink lists’ from all over Germany. However Ernst Rohm, a senior leader in the movement, had been well known for his homosexuality for many years, and Hitler largely accepted it until Roehm’s purging. Burdekin may be reflecting certain early theories of Nazism that linked it to ‘perversion’ among its (male) adherents. Peter Tatchell has pointed out that William Shirer’s classic The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (first published in the 1960s) not only makes no mention of the persecution of homosexuals by the Nazis, but also attacks key Nazis (such as Roehm) as ‘notorious homosexual perverts’ with ‘depraved morals’. Referring to dissent within the Party prior to the ‘Night of the Long Knives’, he says the Nazis ‘quarrelled and feuded as only men of unnatural sexual inclinations, with their peculiar jealousies, can’. Certainly it was not uncommon for anti-Hitler propagandists to make homophobic allegations. For example, in 1933 the exiled Communist Party attempted to discredit the Nazis’ claims that the Reichstag fire was a communist plot by portraying Marinus van der Lubbe, who was arrested for the act, as ‘Röhm’s toyboy’.

Swastika Night’s didactic style means entire conversations on history and philosophy are just laid out on the page for the reader. It starts with a ‘show don’t tell approach’, but reverts to a rather tedious ‘telling’. Nevertheless for all its flaws it is a fascinating and unusual take not only on Nazism, but also the cult of masculinity — which Burdekin saw as having an extreme expression in Nazism. This gives Swastika Night a contemporary significance when considering the aggressive (‘toxic’) masculinity of the contemporary far-right, which Petronella Lee sees in the ‘manosphere’:

Emerging in and around the 2010s, the manosphere is most simply defined as “an online antifeminist male subculture that has grown rapidly in recent years, largely outside of traditional right-wing” circles. It entails a disparate network of websites, internet forums, blogs, and videos that focus on men’s issues, share a chauvinistic orientation, and are united by an emphasis on male victimhood.

Lee decribes the ‘manosphere universe’ as comprised of a variety of different and overlapping circles, including MRAs (Men’s Rights Activists), PUAs (Pick Up Artists), MGTOWs (Men Going Their Own Way), and Incels.

Incel is a portmanteau for ‘involuntary celibates’ — men who define themselves by their inability to find a romantic or sexual partner. While the term Incel did not originate with angry young men being hostile to women, it has now become exclusively associated with that group. The perpetrator of the 2014 Isla Vista killings, 22-year-old Elliot Rodger, wrote a 140 page autobiographical ‘manifesto’, entitled My Twisted World, which consists mostly of extended lamentations about the unfairness of his life in general, particularly his inability to get a girlfriend of sufficient attractiveness to be worthy of a man of his ‘status’. Rodger is obsessed with status and the hierarchy in which he believes he should be at or near the top (at one point he describes himself as ‘close to a living god’). A frustration with an inability to socially interact with women becomes a conviction that they are ‘withholding sex’ from him: an aggressive act. He concludes that

[t]here is no creature more evil and depraved than the human female. Women are like a plague. They don’t deserve to have any rights. Their wickedness must be contained in order to prevent future generations from falling to degeneracy.

The social vision he goes onto describe is disturbingly similar to that imagined in Burdekin’s future society.

I have created the ultimate and perfect ideology of how a fair and pure world would work. In an ideal world, sexuality would not exist. It must be outlawed. In a world without sex, humanity will be pure and civilized. Men will grow up healthily, without having to worry about such a barbaric act. All men will grow up fair and equal, because no man will be able to experience the pleasures of sex while others are denied it. The human race will evolve to an entirely new level of civilization, completely devoid of all the impurity and degeneracy that exists today.

In order to completely abolish sex, women themselves would have to be abolished. All women must be quarantined like the plague they are, so that they can be used in a manner that actually benefits a civilized society. In order [to] carry this out, there must exist a new and powerful type of government, under the control of one divine ruler, such as myself. The ruler that establishes this new order would have complete control over every aspect of society, in order to direct it towards a good and pure place. ...

The first strike against women will be to quarantine all of them in concentration camps. At these camps, the vast majority of the female population will be deliberately starved to death. That would be an efficient and fitting way to kill them all off. …

A few women would be spared, however, for the sake of reproduction. …

In death Rodger has inspired others, including another killer Alek Minassian (perpetrator of the ‘Toronto Van attack’ which killed 10 people). Minassian posted online that he was launching an ‘incel rebellion’ and praised Rodger as the ‘supreme gentlemen’.

Being an Incel appears to be mainly a young man’s game — strongly associated as it is with online platforms such as Reddit. The older person’s belief system combining hostility towards women with status anxiety is Men’s Rights Activism. Often called ‘MRAs’ — men’s rights as a contemporary concept has become an aggressive assertion of traditional patriachal social relations. MRAs are particularly incensed by no fault divorce, and the belief that the family courts favour women, on matters such as access to children. Men, they argue, are more oppressed than women in a misandrist world, and therefore require their own ‘liberation politics’. However their version of liberation is zero sum: women’s increased agency in relationships means male freedom is reduced.

MRAs are not exclusively men. They have female supporters such as high profile former journalist and editor Bettina Arndt in Australia. To the extent that ‘Men’s Rights’ has a criticism of the day-to-day operations of the legal system, which often leaves the working class worse off (including working class men), it could be argued that they have a point. However MRAs are only interested in Family Law, in which women might have an ‘advantage’ (a debatable claim to say the least). And instead of coming up with proposals to improve the operation of family courts (such as increased funding to deal with caseloads), they advocate abolishing them altogether, and restoring some version of ‘fault’ divorce which restricts the ability of women to either leave relationships, or claim custody over children. These proposals are often presented as ways of addressing rates of male suicide, and resistence to them is blamed on the elevation of Feminism to an oppressive power in society against men.

On one level making comparisons between the isolated Incels, the self-pitying MRAs, and the organised political movement that was Nazism, seems a stretch. However, when we compare the organisation of far-right politics in the contemporary era with those of the mid 20th century, we are not comparing the right things. The proper comparison is whether extreme ideas have the means to gain increasing acceptance in broader society.

In the pre-digital communications age, mass organisations and political parties acted as transmission systems for ideological views. Overt saturation through propaganda and rallies on a mass scale brought acceptance. In the 21st century however, discussions that would previously have occured at a politcal meeting can now take place entirely online — resulting in radical ideologies spreading far more quickly. Superficially this could appear reassuring. Those ‘radicalised’ by a Reddit community may never leave their rooms to form a political party that can takeover the state.

However, while Incels may be rare, violence against women is not. And the ideas associated with Incelism and ‘Mens Rights’ still influence the broader social and political discourse in malign ways. For example, after the Toronto killings, New York Times columnist Ross Douthat wrote a notorious ‘objective’ article on the Incel worldview entitled ‘The Redistribution of Sex’. Douthat proposed that

Right-thinking people will simply come to agree that [a right to sex] exists, and that it makes sense to look to some combination of changed laws, new technologies, and evolved mores to fulfill it.

In Australia the far-right One Nation Party, despite its high profile leader Pauline Hanson being a divorced woman, explicitly pitches itself at men who feel aggrieved by Family Court outcomes, and its leaders spread dubious claims about male suicide rates being attributable to family breakdown. One Nation will have a six year presence in the Australian Senate after the most recent national election.

So fighting fascism is not just about looking out for increases in support for previously marginal and extreme parties and movements, it also about resisting the increasing acceptability of particular ideas that might not at first glance seem ‘political’. Anxiety about the loss of particular senses of male entitlement and status may seem personal, but it has always had a (sometimes deadly) political impact. A recent study of the sources of Donald Trump’s support found that it derived from the ‘status threat felt by the dwindling proportion of traditionally high-status Americans (i.e., whites, Christians, and men)’ rather than pocketbook economic concerns.

With this in mind, Katharine Burdekin’s novel deserves credit for highlighting an important aspect of Nazism that is often overlooked in popular portrayals. That she did so in 1937, when many Nazi ideas about women and gender roles were not so distinct on the political spectrum, makes her achievement all the more notable. The ‘extremity’ of the misogynist future world she describes of course makes it easy to reject, but the attitudes that might lead to it are not so absent from contemporary culture or politics as we might want to believe. It is common to attribute the rise of fascism to mobilisation about specific grievances and humiliations: Germany’s treatment under the Versailles Treaty; Italy’s raw deal as a ‘victor’ after the first world war etc. Contemporay far-right revivals are linked to issues such as the Global Financial Crisis, refugees, and immigration. However underpinning all these fears are anxieties of status, exemplifed by Eliot Rodger’s certainty about his own entitlement, and anger that the world wasn’t treating him as he thought he deserved. Burdekin saw this being played out by the Nazis not just in their anti-semitism and racism, but also in misogynist violence. The extent that transphobia has been readily adopted by the far-right shows that status anxiety can connect itself readily to new and emerging issues, the more intimately connected to personal identity the better. That intimacy means fascist ideas can overlap narrow, Left versus Right readings of political boundaries far more than we care to admit. You could call it ‘toxic status anxiety’, which Burdekin grimly dramatises by showing how the future Nazi hierachy in Swastika Night maintains its intense hatred for women even centuries after they have been ‘reduced’. In the words of Liz Fekete, Director of the UK’s Institute of Race Relations (quoted by Lee):

Fascism … is an exacerbation, a more militant extension, of the patriarchal relationships between men and women that have persisted for centuries. It is a worsening of the fantasies, the violence, the misshapen desires that the whole system of gender relationships … Rather than a thing, which is categorically distinct from other social and political systems, fascism is a process, which can easily recur, and wherein we can see men, and groups of men, who have commenced the journey.